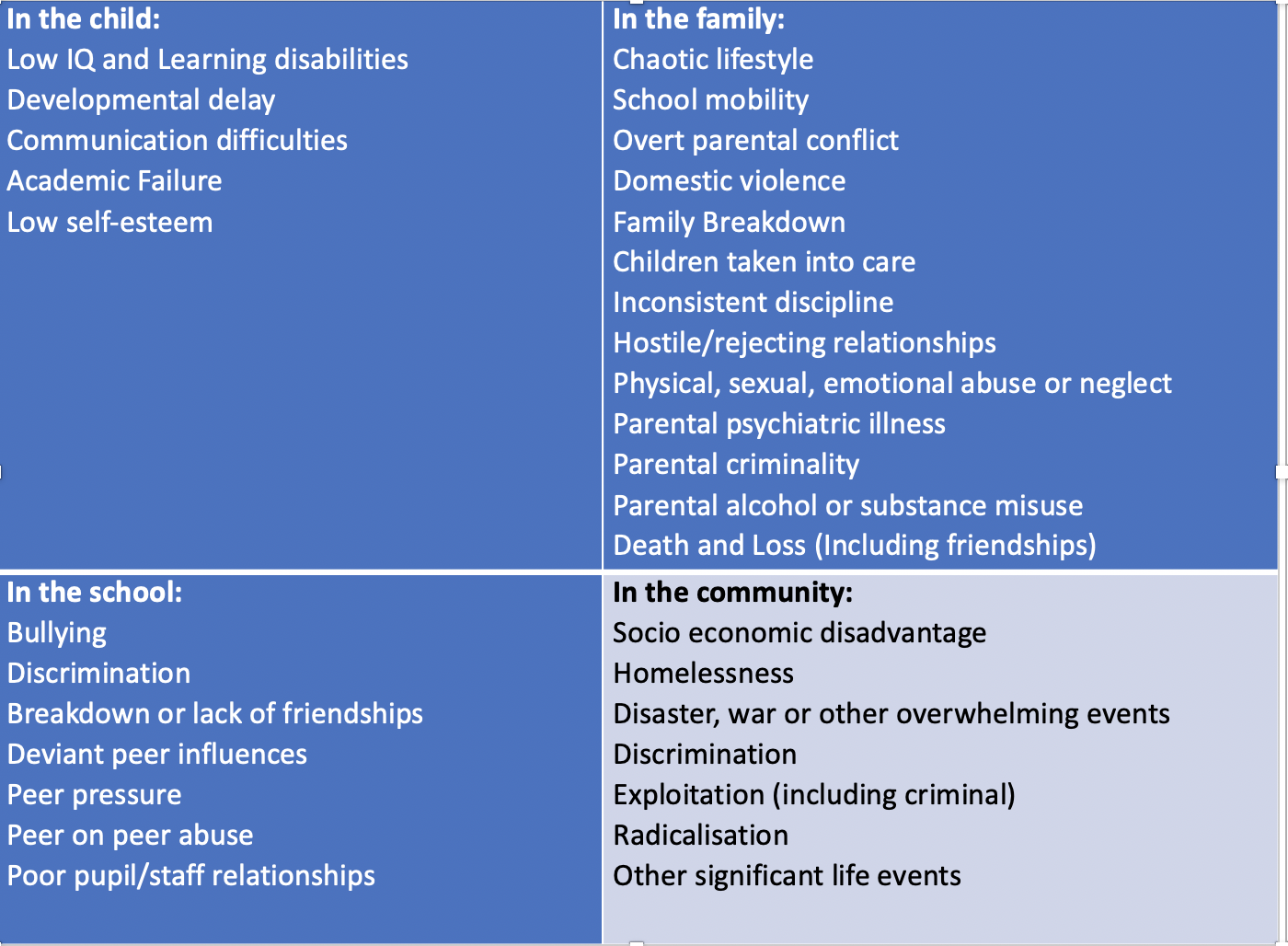

After working in many roles at schools in central London, Amy Herbert, gained a lot of experience at working with children deemed ‘at risk of exclusion’. She then trained as an Educational Psychologist and felt that much of the research on exclusion was focussed on secondary pupils after the point of exclusion. She felt that this encourages a ‘deficit model’ often placing the causes of exclusion as being something lacking in the child or family. Into this context, Herbert (2021) focussed her doctoral thesis on the positive ways in which the system around the child supported and prevented exclusion within a mainstream primary school.

Rather than use a ‘deficit model’, Herbert (2021) chose to look at the positive ways in which the system around a primary school child provided support and prevented exclusion.

Methods

Herbert used a qualitative approach with the aim of giving a voice to pupils, parents and school staff. The study was conducted in large London primary school where proportions of pupils with special education needs and free school meals were above average.

The participants included four pupils were who felt to be at risk of permanent exclusion, their main parent/carer and four staff from the school who knew these children well.

An Appreciative Inquiry (AI) (Cooperrider, et al., 2008) was conducted with each of these groups. This involved taking them through a three-step process resulting in a co-produced positive plan of action for the school.

Firstly, in the discover phase, each participant was asked to identify the factors that they thought were currently in place that supported the child in preventing exclusion. Secondly, each participant was taken through the dream phase where they were asked about the things they would ideally like to see. A thematic analysis was used to identify similarity across the participants views and these were considered using Bronfenbrenner’s (1992) ecological systems theory. Finally, there was a design and deliver phase, where ‘proactive proposals’ formed the basis of a co-produced action plan for the school.

Herbert used Appreciative Inquiry (AI) to give a voice to pupils (at risk of exclusion), their parents and school staff in a large London primary school.

Results

The school action plan is a key outcome of the study, however, I found myself more drawn to the voices of the participants coming out of the discover phase for each group. The main themes and sub-themes are below:

Themes and sub-themes of children’s views on what supports them at school

The children’s views were based around the four main themes:

Support from teachers – This included supporting emotional regulation, support with learning and positive pupil teacher relationships.

Importance of peers – This included having friends as motivators and having positive peer reltionships.

Learning Environment – This included motivators, the availablity of a nurture room, having provision for special interests and good outdoor space.

Self-efficacy – This included being able to take responsibility and self-talk.

These are laid out on pg 65 of the thesis and are them looked at in much more detail. They are well worth a read and the pupil voice shines through.

Themes and sub-themes of parents’ views on what they think works to prevent exclusion.

The parents’ views were based around four main themes:

Staff knowledge and skills – This included having well trained staff, who adopt a flexible approach, have the time to understand and are calming and not controlling.

We work together – Here the parents said that they felt like part of the process, there was good communication and that the staff stood by you.

Whole school ethos/systems – The parents said that it worked well when the whole school took the same approach, staff go the extra mile and there is an individualised approach to inclusion. They felt that the school believed in social inclusion and was firm but fair.

Provision and support – Parents also mentioned the successful use of motivators and the availability of the nurture room. They felt that it was important that their children experienced consistent adults who supported emotional regulation as well as the opportunity for their child to work with speciclaists when appropriate.

Each of these points is expanded beginning on pg 71 of the thesis and again, is well worth a read. One parents said:

“and they was just amazing with him. And I’d watched them like just manage to not control him but calm him. Control was not the word, they calmed him,” pg. 74

Themes and sub-themes of staff views on what they think works to prevent exclusion.

Staff views were organised around 5 main themes:

Whole school ethos – Here staff believed in a nurturing environment which prioritises wellbeing and a staff committed to inclusion.

Approaches to the curriculum – Here they mentioned being able to adopt a flexible approach to the school day, good quality differentiation, support for writing and the use of motivators.

Staff working as a team – Where things successfully supported pupils, staff felt empowered to make decisions, there was good communication and flexibility and that staff within the team had the skills and life experience to respond appropriately when needed.

Learning environment and provision – The availability of the nurture room was seen as positive as was giving pupils space to emotionally regulate. Having consistent staff, who understand the need for a small steps approach and who with the time to respond appropriately was felt to be important.

School systems supporting children – These included the way the school organises their staff roles, their approach to behaviour management, their engagement with outside agencies and the way they work in partnership with parents.

A detailed explanation of each of these points can be found starting on pg 84 of the thesis.

The positive voices of the participants shines through this work and is worth a closer look

Conclusions

Herbert draws the themes of the three groups together and concludes that:

‘The data analysis identified a number of interlinking factors that were successful in preventing exclusion. This included a strong leadership that created an inclusive, nurturing environment by prioritising wellbeing of the children. The staff team showed unconditional commitment to the children that they worked with and felt respected and valued. The support for the children was consistent and an individualised approach was key, including a differentiated curriculum. Restorative approaches to behaviour and a whole school approach ensured continuity and a sense of ‘fairness’. The way that the space was utilised within the school allowed the children to have the space to feel safe and supported to regulate their emotions, forming consistent relationships with the learning mentors. The outside space and use of nature were also a contributing factor.’ Pg. 136-137

Strengths and limitations

I was unfamiliar with Appreciative Inquiry (AI) and have found its use in this case fascinating. It had the feel of a structured, group coaching approach where participants described the current situation (albeit from a purely positive standpoint), create an image of how they would like it to look and then co-produced a plan of action in order to get there.

One criticism of AI is that as it focusses on the positive, some unhelpful negative factors may be ignored. In this study, the use of space to support the emotional regulation of children is seen as a positive. I found myself wanting to ask why the children in these situations needed to regulate in the first place. Was there something going on that could be stopped easily and the need for space then reduced. I wonder if the structure of AI would allow for that to be picked up.

The voices of the children, parents and staff shine through this work and allowed the school to develop a co-produced plan of action in order to celebrate and promote the things that are going well. There should be celebration here. Herbert has a methodology that can be used in a range of situations to provide a positive approach to an issue causing concern.

This is a very small-scale study conducted under challenging circumstances and Herbert acknowledges all the limitations that come with that. She is making no grand claims. She has, however, done what she set out to do. She has added a range of positive, solution focussed voices in a field where it is sorely lacking.

Main Reference

Herbert, A (2021) An Appreciative Inquiry of Factors Within a Primary School that are Perceived to Support Children Who Are ‘At Risk’ of Exclusion. Prof Doc Thesis University of East London School of Psychology https://doi.org/10.15123/uel.89vxw

Other references

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Cooperrider, D., Whitney, D. D., Stavros, J. M., & Stavros, J. (2008). The appreciative inquiry handbook: For leaders of change. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Each month I will send out the way that the latest research and practice impacts on children excluded from school. Sign up below and let me know if you think something needs to be included – Chris